The Social Politics of Imagined Realities

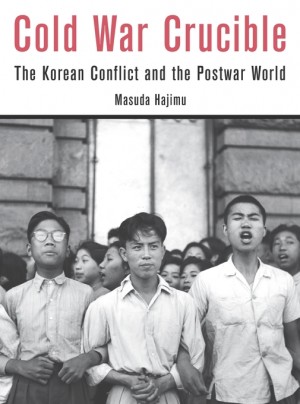

In Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World, new this month, Masuda Hajimu reveals social and political forces normally seen as products of the Cold War actually to have been instrumental in fostering the conditions from which the conflict sprung. Below, he examines how the dynamics he identifies as having contributed to the pervasive global logic of the Cold War can be seen anew in our own time, when the “War on Terror” becomes ever more entrenched as the rubric with which we explain the world.

Cold War CrucibleMany thousands of volumes have been written on the issue of the Cold War. Many other “Cold War” products are available, as well, whether directly related to the history of the Cold War or not. If you go to the Amazon website, for example, you can find nearly 80,000 items related to the term “Cold War,” from John Lewis Gaddis’s history books to a Cold War Veteran license plate frame, to the new album from American indie rock band Cold War Kids. However, none of these books and items, with a few exceptions, dare to explore a simple but fundamental question: What, really, was the Cold War?

Cold War CrucibleMany thousands of volumes have been written on the issue of the Cold War. Many other “Cold War” products are available, as well, whether directly related to the history of the Cold War or not. If you go to the Amazon website, for example, you can find nearly 80,000 items related to the term “Cold War,” from John Lewis Gaddis’s history books to a Cold War Veteran license plate frame, to the new album from American indie rock band Cold War Kids. However, none of these books and items, with a few exceptions, dare to explore a simple but fundamental question: What, really, was the Cold War?

The answer has been taken for granted: It was a global confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States, fought within geopolitical, diplomatic, ideological, and cultural arenas in the second half of the 20th century. The conflict began, it is commonly believed, with the conduct (and misconduct) of top leaders, such as Harry S. Truman, Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong and so on, and ended abruptly with the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s. However, such neat narratives do little to further our understanding of the Cold War, and even less to help us understand our world today.

When I began my project in 2005, I did not expect to write my book in the way I did, but, looking back, I think I was feeling uneasy about the ways in which the history of the Cold War had been written, remembered, and pushed aside. What I tried to do in my book, therefore, was to think about another meaning and function of the phenomenon we call the Cold War, and, in so doing, to deliberate on what it really was. Viewed in this different way, I see the essence of the Cold War world lingering today in our lives and thinking in this age of the War on Terror. In fact, to think about contemporary implications of my book right now is a bit hard and even depressing, because it is so deeply relevant for us, especially in the post-Charlie Hebdo world.

Odd as this might sound, my project’s roots go back to a two-month bicycle trip in the Middle East almost twenty years ago, when I was nineteen years old. It was the summer of 1995, and the media, back then, was quite optimistic about the future of the Middle East because of the peace agreement between the Palestinian and Israeli governments at the end of 1993. What I experienced during my trip, however, was very different. Instead of mutual understanding and peaceful coexistence, I sensed deep-rooted distrust and antagonism among the people I met in Syria, Jordan, and Israel, and realized that popular attitudes on the ground had not changed much, despite diplomatic achievements at higher levels.

Then, just one month later, the Israeli Prime Minister was assassinated. This news was met with surprise by the media, but I wasn’t surprised. Of course, I hadn’t expected the assassination, itself, but I had been convinced of the difficulty of the peace process. This experience suggested to me that diplomatic achievements on the surface did not represent the whole picture, and this realization made me more attentive to the people and emotions behind politics and conflicts.

This interest in the crossroads of war and society and politics and culture has informed my work ever since, first as a journalist and now as a historian. My first book project, initially on the international history of the Korean War, quickly metamorphosed into a broader inquiry into the very nature and meanings of the Cold War. In particular, I developed an interest in the ways in which widespread fear at the time of the Korean War bolstered the specter of World War III, which, in turn, helped to codify the imagined reality of the Cold War world. Furthermore, through my research on various social suppressions and purges around the world, I was taken aback in seeing how ordinary people shaped and used the “reality” of the Cold War on the ground to contain diverse social disagreements and culture wars that surfaced in the aftermath of World War II, transforming policymakers’ discourse into ordinary people’s reality. That’s why I argue in Cold War Crucible that the actual divides of the Cold War existed not necessarily between the Eastern and Western blocs but within each society, with each, in turn, requiring the perpetuation of such imagined reality to restore and maintain social order and harmony at home.

One of my early research projects dealt with the “Yellow Peril,” the late-19th and early 20th century perception of Asian immigrants as a threat to the West. At a glance, it might appear strange to see the evolution of my interest from the Yellow Peril to the Cold War, the former a popular topic among social and cultural historians, and the latter traditionally studied by diplomatic and political historians. Yet, when we look at social politics of inclusion and exclusion against the backdrop of images of global menace, these phenomena appear to have certain commonalities. First, both were, to some extent, realities imagined in times of social upheaval, and, second, both contributed to erecting sorts of “walls” among people and within communities, which functioned to clarify lines between “us” and “them,” thus making it easier to spot and silence nonconformists and purify the worlds inside the walls. In short, what I have been problematizing is the imagined and constructed nature of “reality” and its function in society.

Today, the “reality” of the world we are creating seems to have strong similarities to the worlds of the Yellow Peril and the Cold War. We are observing the crystallization of the world of the War on Terror, which has been fueled by the fear and hatred toward “terrorists” in the post-Cold War era, and particularly since September 11, 2001. It is also a world in which we are seeing the recurrence of the politics of “us” and “them” under the banner of public security, with the construction of new walls between communities, among people, and even inside our minds, which, as in the time of the Cold War, often serves to marginalize diverse social conflicts.

To be sure, what we have seen in recent years—and particularly what we have witnessed in the case of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January 2015—are not empty bogeymen but actual violent assaults, and the degree of “fantasy” differs widely from the times of the Yellow Peril and the Cold War. Yet, looking at the spread of a particular type of discourse and its social functions, I feel that we might be witnessing the moment when the discourse of the War on Terror is just becoming the “reality” of the world, in a quite similar manner that Cold War discourse became an irrefutable “reality” in the postwar era, particularly during the Korean War period. Do we really need such a “reality” in the 21st century?

Once we take off a Cold War lens and re-examine what the Cold War really was, we should be better equipped to see the imagined and constructed nature of our walls, reality, and history. Instead of formulating another imagined reality, we can keep raising questions about stereotypical narratives that tend to simplify complex stories and prevent us from thinking further. How real is our “reality”? How and for whom are the images of threats composed and circulated? What are the social needs—or self-sustaining dynamics—of such imagined realities? Who creates walls and for what purposes? It’s not vain for us to keep raising such questions because, as our experience of the making of the Cold War world tells us, each of us is not just a victim of such an imagined reality but, indeed, a creator.